Kateryna Nosko: Your last slim book, called Nearness, reflects a phenomenon of nearness in the context of the coronavirus-crisis. Could you please specify this notion a little bit more. Which exactly nearness do you mean here, since nearness and presence (co-existence) of bodies in one space are not the same? Furthermore, sometimes emotional nearness doesn’t require shrinking of physical distance.

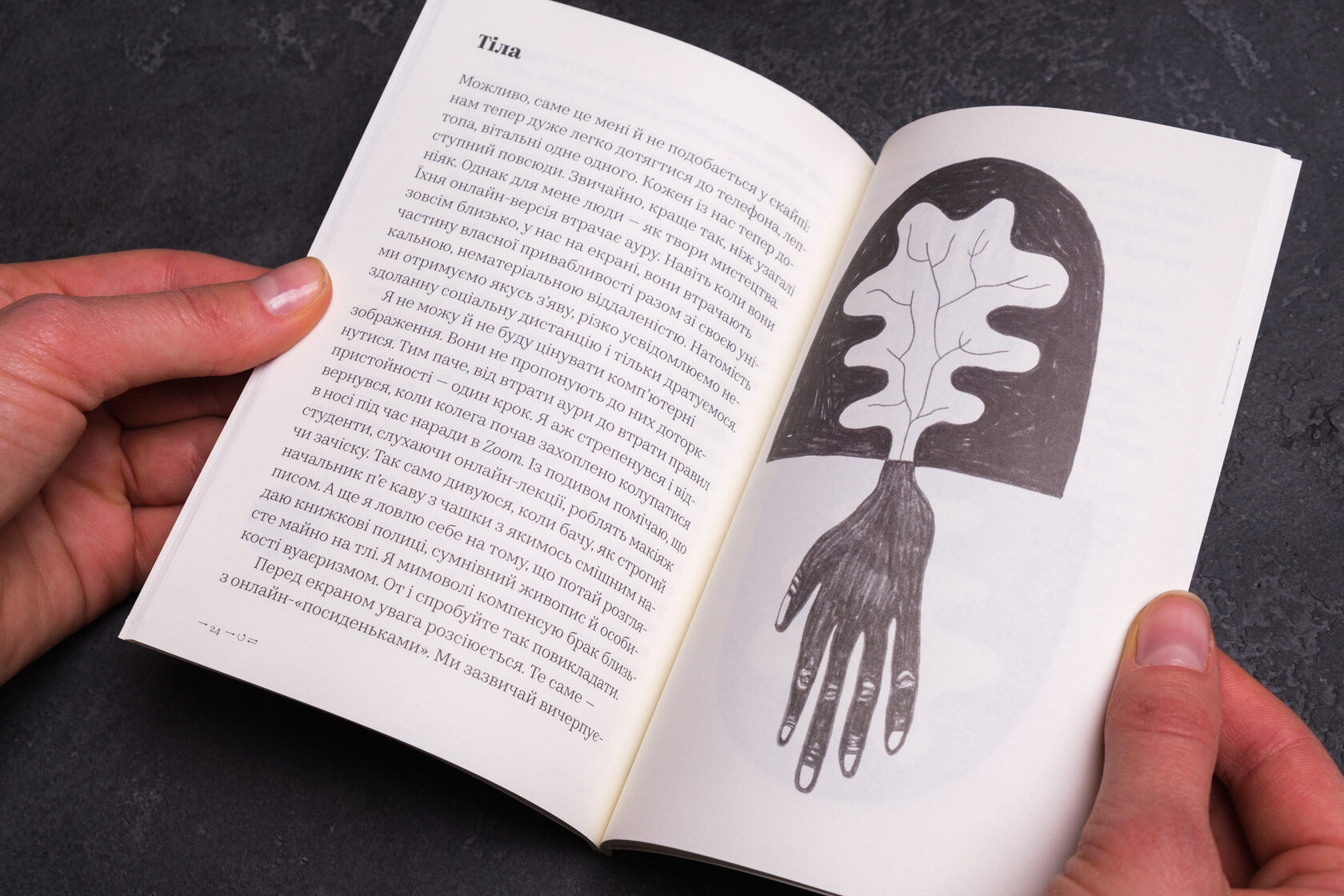

Pascal Gielen and Marlies De Munck: We understand nearness in the first place as a physical proximity. So, it has certainly to do with ‘co-presence’ in a certain space. We think this physical co-presence is a vital condition to understand a person in his or her ‘totality’, as being part of a particular cultural-historical context and contemporary condition. But indeed, co-presence is only a possible condition to get near to someone, and in itself not a sufficient one either. So, nearness does not equal physical co-existence. Things like attention, empathy and a willingness to open up to the other, are just as important. So, we also do not want to reduce nearness to ‘emotional nearness’ either. What particularly interests us in this text, given the current circumstances of the pandemic, is the visceral or intuitive information you can only get by seeing and hearing the movement of the body, the expressions of the face, the gesticulation of hands, the timbre of the voice,... We classify this as aesthetic information, as in ‘aesthesis’. Nearness then implies a total experience of all the senses. And it’s this aesthetic sensation, we believe, that can make an encounter ‘humane’ in the old sense of that word.

About a year ago our vocabulary was enriched with such notions, as 'social distance', 'coronavirus crisis', 'lockdown'. Cultural institutions tend(ed) to open and close in turns. Cultural managers had to invent hybrid formats. What main trends in functioning of an art sector do you see today, and what threats does it mean for the future?

We are afraid that our encounters will be increasingly mediated by digital tools in the cultural sector and even more in education. As mentioned in our essay we are not blind to the opportunities of the booming digitalization catalyzed by corona. We point at ecological, economic, and efficiency advantages. But precisely because of the economical convenience - the expected efficiency and financial gains - we are afraid that some crucial aspects of culture and education will be increasingly overlooked, and who knows completely forgotten in the end. One of these aspects is the vital importance of nearness in these contexts, as we just described: the total picture and complexity of a person or piece of art in its socio-cultural context and historical materiality. Besides, we’re also afraid that art will be put even more to the margins of society because of Covid-19. The pandemic seems to facilitate the already existing conviction of subsidizing governments that we do not need so many live events, and that digital presentation can be a good alternative for live performances or exhibitions in a physical space. However, what we are witnessing in Belgium today, is that all these live streamings of performances on television and internet channels are terribly boring. Watching a play in a theater hall as part of a physically present audience is simply not the same thing as watching a live stream of that same play at home. You get distracted, your attention span is shorter, there is a distance that has nothing to do anymore with a required aesthetic distance. It simply doesn’t trigger the imagination in the same way. Chances are high that you will not watch it until the end, but rather turn to Netflix where you find material that was never intended for a live audience in the first place. Here, the ideas of Walter Benjamin about technical reproducibility come in again as acutely topical. We see how technological evolution changes the core of art forms. So, live art runs the risk of losing its public and civil function, even after the pandemic. Moreover, we can already witness economic difficulties and psychological problems among artists. Many of them lose income, but also get depressed because they cannot share their creativity anymore and they cannot rehearse properly. We are afraid it will take a long time to recover from this mental and economical state of precarity.

How did the situation in a creative sector change with a Covid-19-switching of living modes (what was earlier 'home', became a place of work)? What happened with a horizontal 'flat world'?

We think the liquid flat world as described in the book Creativity and other Fundamentalisms became even more floating and more flat because of Covid-19. We all experience how we can superficially surf on the internet nowadays, from one virtual event to another. We can combine several meetings, conferences and lectures at the same time. We can eat, talk, sleep and do so many other things while we are watching a so-called live performance on the www. So, concentration and focus become even more diffused. But also engagements and investments of time, intellect and energy to listen or to look at a work of art seem to evaporate. And at the same time the border between life and work, leisure time and labor is completely blurred. We could say that the pandemic functions as a catalyst for the post-Fordist condition we were already working and living in. It becomes even more the responsibility of the isolated individual to decide where and when to draw a line between work and private life, between public and private life. At the same time there is also the social pressure to work, also to invest a lot of ‘administrative time’ to learn to work with those digital tools. Meanwhile you cannot do your ‘real job’, the things you are good at and that used to give you the drive, the energy and the enthusiasm to work. Sadly, it seems that many people are just settling into this new situation, waging practical gains against psychological costs, conveniently forgetting about the long-term effects on their mental and physical sanity. So, we expect another serious pandemic catalyzed by corona, a pandemic of massive burn-out and depression. It may take much longer to overcome this psychological pandemic because just an injection of a vaccine will not be sufficient to combat this mental virus.

Before the pandemic, when people had been able to travel, and give offline lectures, they easier agreed to take part in online-events. We’ve noticed though that recently people tend to avoid such activities, since online-participance became so abundant. For instance, we received a denial from one Italian artist, whom we invited to give a lecture for Ukrainian-speaking public. He said, he had enough of all that. After that we received at least five more similar reactions and answers on our proposals. So the question is: what can we do in this situation, since online-presence is almost the only possibility for public appearance today? Where this self-refusal from online-activities can lead us to?

We understand the response of the Italian artist. We sometimes refused to take part in online lectures as well. And whenever we had the choice, we definitely opted for physical meetings and live lectures.To be on the spot when you give a lecture or do a performance is crucial to communicate with the audience and to understand each other as full, particular human beings. Our former argument and plea for nearness remains at stake here. Besides, there is something like ‘digital fatigue’ and one can notice how it has become a general state among colleagues and friends. So, refusing online events now and then is also a matter of protecting ourselves and our mental state. On the positive side, we hope people will invest more in their local community, in more in-depth encounters, not just because they feel the emptiness and frustration after all these digital meetings, but also because they realize the danger of social isolation that comes with leading your life online. Also, as members of the academic world and the cultural field we have become more aware of our ecological footprint, and should think twice before taking an airplane. In this regard as well, investing in local networks and communities is a precious and even necessary thing. These are serious arguments against globalization. And even though we also see the advantages of internationalization, the current crisis reminds us once again of the dangers and long term risks of overlooking your local community.

What were the measures of Belgium’s authorities in the educational and cultural fields since the beginning of the crisis? And how do they support these fields now?

Probably the measures were quite similar to other European countries, evolving from total lockdown to semi-lockdowns and curfews. In education we also see variations going from complete digital distance learning over hybrid forms to live courses. Cultural venues were first all closed, and then the museums were opened again under strict conditions. Theatre and live concerts are still prohibited at the moment. The Flemish government made an extra fund available for the cultural field, but we are afraid they will recover the extra money by budget cuts in the near future. Moreover, the requirement to obtain these extra fundings was the promise of live streaming and digital dissemination of the artistic results. As we have tried to argue in our essay, these technical demands will definitely have a direct effect on the nature and quality of the artistic results. De facto, artists who are naturally inclined towards digital formats, whether it is because of the sort of art they make, or just their personal knowledge of technology, are financially encouraged and favored over artists who have until now invested in live, unmediated performances. The technology influences not only the quality of sound and image, but also for instance the number of people who can be involved in a production. Solo artists, for instance, will generally encounter less difficulties compared to large theater companies to adapt their performance to online formats. We are very curious, and of course a bit concerned, about the outcome of all this.

In the Nearness you write that distant learning and teaching are difficult. Could this difficulty be explained with our prior experience (experience of teaching and learning offline, we had before)?

One thing we found is the great resemblance and deep connection between art and education. At least, regarding impact and connection with other people. It wouldn’t be wrong to state that art is always also a means of learning and thus a form of education. Or, the other way around, that there are numerous ways to learn in life. Solitary reading, for instance, can be an utterly instructive and deeply enriching experience. So, we don’t need to become defeatist and declare the end of education now that we’re going online. Nevertheless, there is a sense of ending now that we have turned to virtual classrooms and online learning environments. And we are convinced this is much more felt by all those who have formerly experienced the deep satisfaction that can come with the traditional classroom setting ‘in real life’. When successful, the latter comes very close to an artistic live performance. The enthusiasm of a teacher, the shared arc of tension, the feeling of togetherness - the sense of going through an experience together - the simultaneous experience of sharing the same object of focus and the aim to reach a shared insight, to share your knowledge… all these are aspects of education that require a live setting, where you can sense the presence of the others. The nearness of teachers and students, the sharing of one space and time have a ritualistic, irrational side that is easily forgotten in textbooks on education. Of course, we know that live education isn’t alway like that. In fact, these ‘exalting’ moments of inspiration are rather the exception, but it is something you constantly aspire to as a teacher. The ambition to make a difference and to touch the hearts of your students, is something that keeps teachers going. The conviction, also, that in the long term these moments can really make a change in someone’s life. And to be honest, until now the online teaching environment, with its empty, anonymous screens and voiced-over power-pointpresentations, has never come even close to that experience.

You wrote that offline-events are important, in order to be in tune with each other. What difficulties do you see in online-discussing of ideas that unite people?

We think that online discussions can be more superficial than offline-events, but we know from scientific literature on e.g. social cohesion that people can unite of course without meeting each other physically. This is called ‘ideal cohesion’. So, by communicating ideas of a common culture, by speaking the same language or by promoting national art or sports you can unite people without physical contact or nearness. But what you miss in this is the collective breathing, the collective rhythm of moving together or having the experience of being silent together and to concentrate together. We think you need at least moments or rituals of collective gathering in museums, theaters or festivals where you can in a way celebrate your collective being in the world. The problem with online gatherings is that they limit the experience to an individual experience. Maybe we can see the same performance but we all respond isolated in our homes to that event. So it’s much more difficult to build a feeling of togetherness. Also the experience of what we call ‘urban intimacy’ is missing online. It means that you can be together with people because you’re interested in the same things like the same art, while you experience in real life that the people who share that interest with you can still be quite different from yourself. This is an experience that requires you to keep your mind open and to question your own unconscious presuppositions about other people. At cultural events you can join and enjoy the same interests with others without being friends with them. Some of those in the same public you wouldn’t even want to meet in a private context. Urban intimacy makes it possible to feel in a way connected or even ‘unified’ with other people without needing more or real intimacy. This experience is very important to accept differences in unity. One effect of a purely imagined, virtual togetherness, is that you are no longer confronted with these real differences.

This crisis reaches all of us. Could we say, we are witnessing the process of re-coding of such notions, as care, trust, and maybe even sensibility?

At least we could say that the pandemic made us realize how important care is and also how important our health care system is. So, we hope the need to invest in it rises higher on the political agenda again, after the enormous budget cuts in healthcare and the deconstruction of the welfare state. But considering trust, we are afraid that the governmental measures and public opinion are pushing us further towards a state of distrust.The illusion and desirability of total control has taken hold again over many, and we fear this comes together with a deep and systematic distrust of all forms of ambiguity or deviation of the norm. Nowadays we are confronted with citizens, neighbors and even friends and family members who report or even betray each other. This behaviour is actually stimulated by the government and mainstream media, but also by the strongly moralizing and condemning tone of public opinions, on internet platforms and in the endless social media chit chat. So, re-coding? Yes, but from trust relationships perhaps more into the direction of fear and paranoia.

Could you name some art-projects, created since the pandemic beginning, that reflect (conceptualize) new changes in the world?

We don’t know so many examples yet, perhaps it is still a bit early to recognize the true nature of the changes we are experiencing. Of course people write books about their corona-days, either happy with the slowing down of life, or desperate about the isolation and loneliness. But in fact, these are feelings that have always existed. Perhaps, we will witness how artists create new sensuous and symbolic forms to embody and express the particular feeling, taste and experience of these pandemic times. Or, ‘corona-art’ may become something nostalgic, a shared experience, after all, that we can look back to and will thus unite our generations? Certainly, there are interesting artistic experiments going on with the new technologies, e.g. Zoom-compositions and all sorts of interactive performances that use online platforms. At the moment, we are following a contemporary music ensemble, the Belgian Nadar ensemble, and their composers to find out how they are dealing with this new reality. We try to understand how they attempt to break through the digital wall, but also how they try and learn to embrace it and turn it into a new musical instrument on its own. These are certainly exciting evolutions to follow up further!

Nearness

Ukrainian version

Authors: Marlies De Munck, Pascal Gielen

Foreword: Borys Filonenko

Translation from English into Ukrainian: Yaroslava Strikha

Copy editing: Tetiana Krushtalovska

Proofreading: Olena Tykhonenko

Drawings: Lotte Schröder

Design: Uliana Bychenkova

110 х 155 mm

48 pages

500 copies

2021